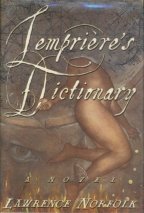

Lempriere's Dictionary (by: Lawrence Norfolk)

I'm actually not finished with this particular volume yet, and I'm not actually sure that I plan to finish. Actually.

Lempriére's Dictionary one of those books that are admirable in their ambition, but are awkward in the attempt. (It appears that today is repetition/assonance day. So let it be written...)

I picked it up because as I was reading A.S. Byatt's Possession on the "eL" in Chicago, my good friend noted that Lempriere's Dictionary was one of Byatt's favorite novels. Since I had fallen into a passionate love affair with Possession, and since this same friend had advised me to read Byatt, it seemed only fitting that I should read the literature that my new favorite spinner of tales so admires. It begins delightfully, with a bang, as it were, and I can certainly see the attraction for a writer of Byatt's interests, that is, investigations into classical literary endeavor and "inside jokes" that assume the reader is familiar with all of the literary and classical allusions the author makes.

Norfolk is, without a doubt, an accomplished scholar in the field of classical literary studies. The sheer scope of his references tell of a bright, interested mind and a doctoral (at least) level of intense study and passion, and he crafts a fascinating, and well-wrought, mirror-story of a young man of the 18th Century caught in a web that reflects and is connected to not only the story of his ancestors, but that of the ancient Greek mythologies - the good ones, the dark ones, like Danae and Prometheus, rather than the familiar and somewhat light-hearted Narcissus and Persephone. Norfolk, like Byatt, also has a flair for turning a quiet phrase, a short sentence at the end of a chapter or a section, into the eerie voice of premonition, or serpentine hissing of dark malevolence. He conveys violence in a chillingly soft voice, and obsessive infatuation is a threatening shadow just at the edges of sight, but ever-increasing.

Thus, in terms of language, imagery, style: Norfolk is a master. He knows language, and he knows his classics. He kind of makes me wish I could read in Greek…

The story is something like this:

A young man, John Lempriére, son of Charles Lempriére, lives in a little country house in the, well, French countryside. I don’t think they’re actually French, though their surname seems to indicate so; they speak English, and John has no trouble when he gets to London. But I get ahead of myself.

John Lempriére, a real 18th century scholar, has an overly active imagination and a voracious interest in classical Latin and Greek literature. He is engaged to instruct the local lord-type-fellow in this field, which is great, because John is in love with said lord’s daughter, the gorgeous and lively Juliette. His father is murdered in a fashion that corresponds, in John’s mythos-bent brain, to the tale of Acteus and Diana. John then heads to London to begin his dictionary of classical characters. Then, the plot thickens. A bit too much, actually. My friend, Jenna would say that Norfolk added a bit too much corn starch to the recipe and got dumplings instead of sweet-n-sour sauce.

Apparently, there is a conspiracy amongst not only the merchants of the East India Company and some dastardly evil-doers, but also amongst classical historians. I am currently slogging through a section in which I can’t tell if the pirates are good guys, bad guys, or comic relief, and the glowing algae isn’t helping. Yes, I’m serious. And, while there is such a thing, I am still trying to discern the reason for it’s presence at this juncture in the novel.

John’s attraction to the mystery of the conspiracy is encouraged by his own vision of the violence in London, the murders, riots, and wild parties as concurrent with the classical tales of which his dictionary is composed. I use “concurrent” intentionally, because it seems as if John cannot, or will not, delineate the mythology from the present terrors, and I am therefore stranded in-between my understanding of the ultimate reality of the 18th century story and my shaky grasp of the ancient traditions and their implications.

I won’t say that it’s a good read; its classical allusions are far too erudite, its plots and subplots so convoluted (Publisher's Weekly calls it a “choked jungle” and “bloated”), and its ambition so exceeds its construction that reading is mostly hard work. I’m a pretty smart gal, and I can hold my own in tough literature, but there’s a reason I’ve been putting off reading Ulysses and its ilk, and it ain’t ‘cause I don’t think I can handle it. I just wonder if the effort will pay off. Obviously, Lempriére’s Dictionary is hardly a Joycean work of stream-of-consciousness or absurdity, but my point remains the same.

I will say that, at times, Norfolk sweeps me up in imagery and poetry, and several “moments” in the story have stayed with me throughout the reading and the current occasional forays back between the pages. If you do decide to start in on this one, watch for the scene in the ceramics warehouse. Quite unnerving, I must say.

On the KTG Zeusian Bolt scale, this rating is based only on a "thus far," of course, since I haven't completed the book. It earned the second Bolt for the ingenius nature of the parallel plot structure, similar to that which I loved in Possession. (out of 5):

Craft: +++

Plot/Story: ++

~~~~~

Overall Rating: ++

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home